Witnessing For The Faith In China's Prison

By George M. Anderson

AMERICA, July 29, 1995

![]()

Reprinted with permission of Rev. George Anderson, SJ and American Press, Inc. 106 W. 56th Street, New York, NY 10019. Copyright 1995 All Rights Reserved

![]()

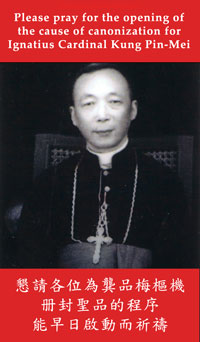

On a cool and cloudless day in late May, a triple jubilee Mass was celebrated at St. Mary's Church in Stamford, Conn. The liturgy marked the 65th anniversary of Cardinal Ignatius Kung's ordination to the priesthood, the 45th of his Episcopal ordination and the 15th of his elevation to the College of Cardinals. What made the occasion particularly memorable, however, was the fact that the principal celebrant, Ignatius Kung Pin-Mei, had undergone 30 years of incarceration, from 1955 until 1985. He was in prison when he was named a cardinal - in secret - by John Paul II in 1979.

Equally remarkable was the presence of a number of others, both priests and laypeople from as far away as Canada, California and Taiwan, who had also spent years in China's prisons and labor camps during the same period. At a dinner in the church hall after the Mass, it was pointed out that the total years of incarceration of those present from the Shanghai Diocese would come to more than 300 years.

Speaking for the laypeople present, Philomena Hsieh said that many among them, including herself, had spent their youth "in dungeons and fields, performing hard labor. Our education was terminated...Our families were broken." Facing Cardinal Kung at the table where he was seated for the dinner, she noted that it was his example that had given them the courage to persevere.

The story of their courage goes back to 1949, when the Communist Government assumed control of China. In the years that followed, repressive measures were taken against a number of religious groups; but the Catholic Church was a particular focus of the new Government's attacks because of its ties with the Vatican - regarded as a foreign power with dangerous influence over the minds and hearts of the people. During the early 1950's, foreign priests, brothers and nuns were expelled. Some who remained were incarcerated, as were many of the native clergy.

The latter had been forewarned. At a retreat for priests, Bishop Kung had told them: "You must not have any more illusions about our situation....You have to face prison and death head-on. This is your destiny. It was prepared for you because Almighty God loves you. What is there to be afraid of?" Nor was it only priests who were targeted. Many laypeople active in organizations like the Legion of Mary, which the Government regarded as subversive, were to be subjected to the same treatment as those in religious life.

Given the tensions that prevailed as the repression became more severe, it was with considerable boldness that Bishop Kung declared 1953 a Marian year throughout his diocese. One of the scheduled events was a special evening of devotion to the Sacred Heart of Jesus for the young Catholic men of Shanghai. Just hours before the event was to take place in the cathedral, Government troops barricaded the main streets in the surrounding area. But the men came by foot, assembling in the square outside and packing the cathedral itself. As the bishop moved through the crowd, some of them surrounded him as a protective escort. After the devotions inside had concluded, he emerged to lead the stations of the cross, followed by leaders of the youth groups carrying a large wooden cross. The evening ended with the people chanting their personal support, despite the presence of the police.

Finally, two years later, on the night of Sept. 8, 1955, there was a massive sweep by the Government that resulted in the arrest of seven diocesan priests, two Carmelites, 14 Jesuits and 300 laypeople. Philomena Hsieh, then a university student active in the Legion of Mary, was among them. Bishop Kung was arrested too. Spotlights shone on the exterior of his residence as security police climbed the surrounding walls. Others guarded the doors. Handcuffed, he was taken away to jail. A second, larger raid on Sept. 26 led to the arrest of another 10 parish priests, nine more Jesuits, 38 seminarians, five nuns and 600 lay man and women.

Like the others arrested, Bishop Kung was known by a number. He had two of them. The first was 1423, then later 28234. Not until five years had passed was there even a trial. Found guilty of treason, he was sentenced to life in prison. His offense had been two-fold. First, despite an offer of immediate freedom were he to do so, he consistently refused to renounce his allegiance to the Pope and to sever all ties with the Vatican. Second, he would not recognize the validity of the Chinese Catholic Patriotic Association, which the Government had by then established in an effort to suppress the legitimate Catholic Church.

To join the Patriotic Association, priests had to sign a statement relinquishing their ties with the papacy. Only after this would they be allowed to function as priests. Though most chose to remain part of what they refer to as the underground church, some did acquiesce. Consequently, having established a division in the Catholic Church, the Patriotic Association remains a source of great difficulty for the Vatican. Adding to the difficulty is the fact that the Government began appointing bishops of its own, subject to the control of the National Religious Affairs Bureau.

For 30 years, Bishop Kung - who remains to this day the Bishop of Shanghai - was allowed no letters and no spiritual books, not so much as a Bible. Nor was he allowed to celebrate Mass, receive the sacraments or have visitors. Representatives of international humanitarian organizations repeatedly requested to see him, but were always refused. As the years passed, his incarceration increasingly came to be seen as a universal symbol of the struggle for human rights. But so complete was his isolation for three decades that, following his eventual release and his arrival in the United States in 1988, he told a reporter for a Connecticut newspaper that the guards passing his cell were ordered to look the other way; even that degree of contact with other human beings was denied to him.

In a sense, however, he was not entirely alone. Others were suffering with him. A main concelebrant at the May 27 liturgy was Archbishop Dominic Tang Yiming of Canton (who died of pneumonia a month later on June 28 in Stamford, Conn.) A Jesuit, he was officially exiled by the Chinese Government after Pope John Paul II appointed him archbishop in 1982. His own 22 years of imprisonment coincided with Ignatius Kung's, as did the many years behind bars of others arrested during the same period. Like Bishop Kung, he had shared the sense that incarceration was to be a part of his vocation.

In his memoirs, How Inscrutable His Ways! 1951-1981, Dominic Tang writes of a Chinese nun who told him at the time of his appointment as bishop: "Your vocation to be a bishop is a vocation to be imprisoned." Her observation led him to reflect: "I always asked God for the grace to realize this vocation." As with Cardinal Kung, the grace was richly if painfully granted. The two indeed had much in common.

Like Ignatius Kung, Dominic Tang, during the years of his imprisonment, was not permitted to write or to receive letters, nor was he allowed visitors until a few months before his release in 1980. His separation from the outside world was complete to the point that his family and friends presumed him dead, and his Jesuit brothers in Hong Kong had Masses said for the repose of his soul.

Dominic Tang's life in prison during these hidden years was physically as well as psychologically hard. "We would shiver all over with hunger," he wrote, and so low in nutrients was the food he received that he developed beri beri. While at the Wong Wah Road prison - one of several in which he was confined - his cellmate was a deranged man. "Once he came over to me and vigorously slapped me on the face, so that my glasses fell to the ground." On another occasion during the night, the same man "came over and walked on me and terrified me as he woke me up."

Prayer was the primary sustaining force. The prayer he recited most frequently was one composed by St. Ignatius of Loyola, founder of the Jesuit order: "Take, O Lord, and receive all my liberty, my memory, my understanding, and entire will, all that I have and possess. You have given them to me; to you I return them....Give me only your love and your grace, for these are enough for me." For those in his position, with their liberty and much else wrested from them, the prayer must have had a particular significance.

In addition to Ignatius Kung and Dominic Tang, there were other priests among the concelebrants at St. Mary's in Stamford who had also been imprisoned for their faith. George Wong, S.J., for example, who was ordained by Bishop Kung in 1951, spent seven and a half years in prison and another eight in a labor camp. Assigned to the rice fields, he worked barefoot in the water with leeches clinging to his ankles. Traces of the scars still remain. His crime? After Bishop Kung's arrest, he refused to sign a statement accusing the bishop of being an "imperialist stooge". "After I refused at the police station, they told me I could go home," Father Wong said in a recent interview. "But I knew it wasn't over, so I prepared a small bundle of clothes and other necessities. That night, at 11:30, they came and took me away."

During those years in prison, he was at one point in a cell with 22 others, so crowded together that when they lay down on the floor to sleep at night, each had to keep his head to the wall, with no space between one man and the next. When the guards learned that he had been teaching the Hail Mary to a fellow prisoner, he was punished by having his hands handcuffed behind his back for 50 days. Although he tried to explain that it was only a prayer, with no political ramifications, the prison authorities believed, because of the name Mary, that the prayer might be associated with the Legion of Mary. And in fact, at his sentencing after seven years, one of the accusations against him was that he had been working with the Legion of Mary as an anti-revolutionary.

A further instance of Father Wong's ministry while incarcerated occurred during the first year, when he was alone in a cell with a former telegraph operator. The man expressed an interest in Christianity. Although talking was forbidden, they managed to whisper, and after three months, the cellmate asked to be baptized. To provide instruction, Father Wong used the back of the cell door as a blackboard, and with a wet rag he wrote on it the prayers he felt essential for the man to know - including the Hail Mary - so that he could memorize them. The actual baptism took place in a corner of the cell, at a moment when they knew the guard would not be watching.

For another concelebrant, Francis Xavier Ts'ai, S.J., the sentence to prison and labor camp amounted to 35 years. Arrested at the same time as Bishop Kung and convicted of the standard charge of anti-revolutionary activities, he was initially incarcerated in Shanghai with six other Jesuits. The interrogations were especially wearing because, as he said during a recent conversation at Our Lady of China Chapel in Queens, N.Y., where he is associate pastor, the interrogators would call for him at any hour of the day or night. His imprisonment included torture. For two months he was kept in a subterranean cell with no light except the faint light from the corridor. The floor was covered with several inches of water, and was called, in fact, the prison of water. He slept on a concrete platform in the center.

Because any sign of prayer, such as movement of the lips, was prohibited, his prayer was necessarily a prayer of the heart. There were two that he used constantly. One he had learned in French: Mon bon Jesus, glorefiez-vous, et le reste importe peu. ("My good Jesus, glorify yourself, and the rest counts for little.") The second was from a Chinese poet: "God is always Lord. There is no place that is not my home" - that is, in prison as well as everywhere else. "With these two prayers, constantly repeated in my heart," he said, "I could endure everything." When at last he came to trial in 1960, he was judged with a group of 13 other priests and a bishop - Ignatius Kung. Then followed the many years of labor camp, working from 6 A.M. to 6 P.M. in a brick and tile factory.

Dominic Tang Yiming, George Wong and Francis Xavier Ts'ai are Jesuits. Cardinal Kung has ties with the Society of Jesus that go back to his youth, when he attended St. Ignatius High School in Shanghai. After his ordination as a diocesan priest, he was appointed principal of the Aurora High School and later of Gonzaga High School. Both, like St. Ignatius High School, were sponsored by the Jesuit order.

As for the situation of the Catholic Church in China today, the persecution has continued. Joseph M. C. Kung, the Cardinal's nephew, who was responsible for his coming to this country, spoke in an interview of the ongoing efforts by the Chinese Government to suppress the underground or unofficial church. He estimates that there are approximately 50 bishops and 400 priests who have resisted the pressure to join the Patriotic Association, and whose lives have for this reason been made extremely difficult.

"In 1989, the underground bishops decided to organize themselves openly into the National Conference of Roman Catholic Bishops, in contrast to the Government-controlled Patriotic Bishop's Conference," Mr. Kung said. "Their purpose was to have a more effective ministry through the sharing of information between them and the underground dioceses, and to inform the world that the Roman Catholic Church in China was growing in spite of the continuing persecution. They never opposed the Chinese Government as such," he added. "They only sought to have the religious freedom guaranteed by the Chinese Government's constitution and by international standards of human rights. Nevertheless, within a few months, they were all arrested in different parts of China and held for varying lengths of time".

Three of the arrested bishops died in custody: Shi Chunjie, Auxiliary Bishop of Baoding; Fan Xueyan, Bishop of Baoding, and Liu di Fen, Bishop of An Guo. According to Mr. Kung, other bishops are being held in detention, for example, Bishop Lee Hongye of the Diocese of Luoyang.

As president of the Cardinal Kung Foundation in Stamford- a group that provides support for the underground church through newsletters, financial aid to priests, seminarians and nuns, and other projects - Mr. Kung is in regular touch with sources in China. He was there last year accompanying a delegation headed by Republican Congressman Christopher H. Smith of New Jersey.

During the course of that visit, Bishop Su Zhiman of Baoding agreed to celebrate Mass for the group in a small apartment in Beijing. Shortly after the delegation left China, the bishop was arrested. In subsequent testimony before the Subcommittee on International Security, International Organizations and Human Rights of the House Foreign Affairs Committee, Mr. Kung said that Bishop Su Zhimin had been detained for nine days and was released only after the intervention of Congressman Smith.

Unauthorized Masses outside Patriotic Association churches are officially forbidden. Many, like the one celebrated by Bishop Su Zhimin in the Beijing apartment, take place in homes or in the open air. "Masses in homes are being raided more and more often," Mr. Kung said. "The people who attend are heavily fined - up to a month and a half's wages - and some are placed in detention." He went on to describe a series of arrests that took place this past Easter in the province of Jingxi, when, over a four-day period in mid-April, between 30 and 40 people were arrested. At the time of our conversation in June, he said that 12 key lay Catholics were still in jail there, including a 60-year old blind man named Zhang Wenlin. During the same series of arrests, two women were so badly beaten that they were unable to feed themselves.

Some underground priests have simply disappeared at the hands of the authorities. Father Chi Huitan who was scheduled to celebrate an Easter Mass for 600 people in an open field near his home in Hebei Province, had been ordered to cancel the Mass and to transfer his con- gregation to the Patriotic Association. He ignored the orders and went ahead with the liturgy as planned. The next day his chalice, paten and other materials for Mass were confiscated, his house sealed, and he himself was arrested. Mr. Kung says his whereabouts remain unknown.

Despite such efforts at repression, however, large numbers of Catholics continue to gather by the thousands at outdoor shrines during the spring. One of the most important is the shrine of Our Lady of Dong Lu, southwest of Beijing. An article in The Washington Post for June 2 described an unauthorized Mass there attended by 10,000 people. Mr. Kung said the number was in fact considerably larger, and that people gather there from all over the country to pray throughout the whole month of May, not just on May 24, when the feast of Our Lady Help of Christians, the high point of the season, is celebrated with the Mass described in the Post article. "Last year as well as this year, the Government blocked the main roads to the shrine, but people came anyway, from long distances, using the smaller roads and even mountain trails and paths."

With virtually all the churches controlled by the Patriotic Association, some underground bishops have tried to build their own churches. Government opposition can take dramatically concrete form. Mr. Kung cited the example of a church one bishop managed to build in the late 1980's.

"Soon after the church was finished, the Government sent in bulldozers and razed it," he said. "But the bishop went ahead and built another one, and this time the people were prepared. They posted lookouts, and when the bulldozers appeared again, they formed a human ring around the church, four deep. The bishop told the security officers, 'if you want to destroy the church, you'll have to kill these people.' After a long standoff, the security officers backed down." Mr. Kung compared the successful outcome of this incident to the much publicized one during the military assault on Tiananmen Square in 1989, when a student holding a flower stood in front of a tank. The tank came to a halt rather than crush him beneath its treads.

Though the persecution of Catholics continues, it has in some respects taken on a different form in recent times. "It's not the way it was in the 1950's and 1960's, when people were imprisoned for 20 or 30 years and more," Mr. Kung said. "Now the tactic is to jail people for shorter terms and to keep arresting them at irregular intervals. It's meant as harassment, since you don't know when the next arrest might be made. When it comes," he continued, "it's along the lines of what might be called administrative detention, because that way nothing is written up formally, as it would be if the matter went through the courts. This is how they try to say that there are no religious prisoners in China, which is simply untrue."

Despite the continuing opposition, Mr. Kung said, the number of women religious and seminarians in the unofficial church continues to grow, though not without severe constraints. Most of the underground seminarians, for instance, have to hold regular jobs in order to support themselves. The Patriotic Association seminaries, on the other hand, which are controlled by the Chinese Government, have far greater financial resources. As a result, their own seminarians are adequately supported both at home and abroad. Some have come to the United States to study in diocesan seminaries here. This apparent concession to the Patriotic Association is troubling to supporters of the underground church like Mr. Kung.

"When he was in Manila this past January," he said, "Pope John Paul II broadcast a message to Catholics in China saying that a true Catholic cannot reject the principle of communion with the successor of Peter. And yet in this country American Catholic priests concelebrate with Patriotic Association priests. Recently, Catholic New York, the newspaper of the Archdiocese of New York, reported that four Patriotic Association priests studying here have been granted full faculties and are therefore allowed to celebrate Mass and administer sacraments at Transfiguration Church in the Chinatown area of the city. Situations like these," he went on, "create confusion for Catholics in China and cause enormous pain to the underground bishops. It appears that the delicate circumstances regarding its dealings with China make the Vatican hesitant to announce a clear policy with respect to the Patriotic Association."

The confusions and lack of clarity in church policy are likely to continue for a long time to come, given the ebb and flow of tensions between the Chinese Government and the Vatican. No diplomatic relations have existed between them since the expulsion of the pro-nuncio in 1951. Officially, the Vatican is willing to recognize only the legitimacy of the Chinese Government in Taiwan.

It is certain, for the present, that the repression of religious groups in China is far from over, and that imprisonment for reasons of faith continues. Hence it was all the more moving to be present at the gathering in Stamford, both for the liturgy itself and then for the dinner that followed in the church hall, with its tribute to Cardinal Kung by Philomena Hsieh. Though not intended as such, it was also a tribute to her and the others present - including Joseph Kung's sister, Margaret - who had known in their flesh something of the experience of the Cardinal. Ms. Hsieh herself spent a year in prison, only to be arrested again in 1958, when she was sentenced to four years in a forced labor camp. There she met her mother, a prisoner too, convicted of not having properly indoctrinated her daughter into Communist ideology.

The Cardinal's name in Chinese, Pin-Mei, means "the character of a flower that blooms in the bitter winter." It is a fitting name, both for him and for the many for whom his example of constancy was a source of strength as they endured their own bitter winters in the prisons and labor camps of China.

But the gathering had a chastening overtone too. The 300 years of imprisonment represented by the men and women who had gathered that day, whether as presider, concelebrants or laity, served as an astringent reminder to Americans, who have always known freedom of worship: We perhaps tend to take this freedom too much as a given, almost casually. For the Catholics of the underground church in China, it is a freedom yet to be won.