Cardinal Ignatius Kung should be hailed as a hero of human rights

He defied China on religion

by Richard Stoecker

Philadelphia Inquirer

March 14, 2000

![]()

Seneca once observed that we admire people who show fortitude in adversity.

Even the most cynical and skeptical critics of the political process find themselves speaking in respectful tones of Sen. John McCain, who endured such hardship for his country in a prison camp during the Vietnam War.

Names like Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Alexander Solzhenitsyn and Wei Jingsheng resound through our age, shattering the emptiness, materialism and superficiality of our times.

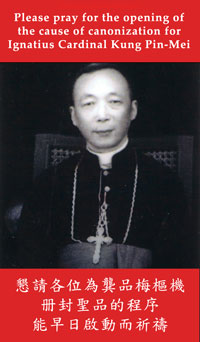

Cardinal Ignatius Kung, who died Sunday at 98, in exile in Stamford, Conn., deserves to be on this roster. The Roman Catholic Bishop of Shanghai, apostolic administrator of Suzhou and Nanjing since 1950, suffered greatly for his faith and inspired others among China's estimated 9 million to 10 million Catholics to do likewise rather than capitulate to government pressure to renounce the essentials of their belief.

Pope John Paul II has compared the Chinese church to that of the early church in Rome, and there have been many points of comparison in intensity of government opposition and the endurance of Christians.

Dietrich Bonhoeffer, from an upper-middle-class German family, a promising young theologian in the '30s, had secured a teaching position at an American university after leaving Nazi Germany. He returned to his country voluntarily, stating that he could not claim a place in postwar Germany if he did not share its trials. After becoming involved in a group opposing Hitler, he was imprisoned and died shortly before the end of World War II. Like Bonhoeffer, Kung had ample opportunities to leave his homeland, China, but stayed there to share the fate of fellow Catholics.

Wei Jingsheng in China and Alexander Solzhenitsyn in the former Soviet Union were important voices for freedom who, through their writings, attempted to call attention to the grievous injustices in their countries. Improvements in Russia have been heartening, but in China there are still all-too-frequent reports of arbitrary arrest and mistreatment of dissidents, religious figures and anyone associated with what the Chinese government calls "splittism."

The term "unlawful search and seizure" has little meaning in Tibet, where authorities do not hesitate to go into private homes or Buddhist monasteries in search of pictures of the Dalai Lama, an important symbol of Tibetan identity, or publications of any kind promoting Tibetan independence. In Tibet, torture has been a common weapon used by officials against Buddhist monks and nuns who would not renounce the Dalai Lama. Catholics who refuse to declare autonomy from the Pope have experienced similar treatment.

Both the Dalai Lama and Cardinal Kung have had to live in exile, the Dalai Lama in India since 1959, Cardinal Kung in the United States since 1987. In 1998, Cardinal Kung's passport was revoked by the Chinese government.

What makes these two men so dangerous in the eyes of Chinese communists?

The Dalai Lama in his extensive travels and speeches has stressed compassion, tolerance and love, themes that were factors in his receiving the Nobel Prize.

Cardinal Kung similarly upheld a teaching of brotherly love, and like the Dalai Lama he was unwilling to lie or compromise. Held for 30 years by the communists and allowed to see only his captors and adherents of the government-controlled church (the Catholic Patriotic Association, as opposed to the Roman Catholic Church), when pressured by officials to renounce the Vatican, he said, "You can cut off my head, but you can never take away my duties."

Among the cardinal's adherents in China were people like the Rev. Shen Lo-t'ian, a seminary student during the intense persecutions of Sept. 8, 1955, who at first was retained forcibly in his seminary for brainwashing.

Arrested in 1958, he refused to sign his arrest warrant. The public security bureau did not allow him water for seven days, after which he vomited blood because of excessive thirst. He was later handcuffed to his own father in a jail cell, and the two men never saw each other again after they were taken away to separate labor camps.

Shen did heavy work at a state labor farm, despite tuberculosis, gastric disease and dropsy. His ordination, occurring only a few years before his death in 1992, has to be among the most hard-earned in anybody's knowledge.

Kung was a worthy leader of such Catholics, inspiring countless instances of endurance, of years in the labor camps working inhuman hours, experiencing hunger, sacrificing their health, undergoing brainwashing sessions, torture and sometimes death.

It is fashionable in the United States to explain everything in life, everything people do, in terms of economics, social mobility, the desire for formal education or security of one kind or another. Some say trade and American investment will solve the human-rights problems of China and answer every need there, as they presumably imagine it to do here.

But human beings are not so constructed. Cardinal Kung's niece, Margaret Chu, before her arrest in 1958, scored high on a university entrance exam in China, but when she did not acquiesce to the government's demands that she renounce her uncle and her faith, she lost her opportunities in the new China and spent more than 20 years in the notorious laogai or labor camp system. She lives in the United States today, married to a man who was also a laogai prisoner, one of eight brothers all but one of whom served time as a prisoner of conscience in China.

The life and sufferings of Cardinal Kung and the millions of underground Roman Catholics and adherents of other religions in China are proof of the triumph of ideas over force, of conscience over terror.

Freedom of worship was one of the four freedoms for which we fought World War II. It should be regarded as no less important than the other three freedoms, freedom from want, freedom from fear and the freedom of speech and expression.

Kung should be remembered as a hero in the continuing worldwide struggle for human rights. His name should be well-known in all countries, and especially here.

In a political year, I hope that we will examine carefully the statements of major candidates on human-rights problems in China. This would be one way of honoring the memory of Cardinal Kung, a fitting symbol of integrity for our time.